Protection for South Florida’s Water Supply Is Crumbling

Published 4 May 2020

Communities at the southern tip of Florida depend on a system of water control structures known as the L-31E for protection from the sea. Under the strain of 60 years of rising sea levels, climate change and neglect this protection is beginning to crumble, allowing sea water to flood into the aquifer that provides fresh water for the region. Unless water managers act soon, people living in Homestead, Florida City and the Florida Keys could lose their supply of drinking water.

The L-31E is an original component of the Central and Southern Florida Flood Control Project. This is the regional system of levees and canals constructed in the 1960’s for flood protection and water supply and to support economic growth and development in South Florida.

The L-31E consists of a levee and a canal that follow the shoreline of Biscayne Bay. The L-31E protects southeastern Miami-Dade County from encroachment by the sea, both above ground and through the aquifer below.

Above ground, the L-31E levee prevents extreme high tides and storm surge from flooding the low-lying area east of the coastal ridge. In 2017, this levee prevented Hurricane Irma’s 4.5-foot storm surge from flooding the area east of Homestead and Florida City.

Below ground, water managers use the L-31E canal to create a hydraulic barrier keeping sea water out of the surficial aquifer. The L-31E canal is located on the inside of the levee. As long as the water level in the canal is maintained higher than the water level in Biscayne Bay, the direction of seepage under the levee is toward the bay.

Water control structures installed along the length of the L-31E levee are used to regulate water levels in the canal. These act like gates between the canal and Biscayne Bay. The L-31E canal is connected to the regional drainage system. Runoff from rainfall collects in the canal, and when the water level in the canal gets too high, the control structures are opened to allow water to empty into Biscayne Bay.

Sea level rise since the L-31E was constructed has created problems. Generally, the problem is water levels in the canal rising too high. Sea level is about 6 inches higher than when the L-31E was built. Higher water levels in Biscayne Bay impede flow through the control structures when they are open, and this reduces the ability to drain excess water from the canal. High water levels in the L-31E canal increase the risk of flooding in coastal communities.

Problems at the S20 structure

A different problem affects the southern end of the L-31E. At the S20 structure water levels in the canal are too low to protect the aquifer, and sea water is infiltrating into the L-31E canal.

The S20 structure drains the Model Lands basin, a small, hydrologically-isolated drainage basin located east of Florida City. The S20 structure is used rarely to drain excess water from the canal. Water levels in the canal fluctuate widely in response to rainfall and evaporation over the basin.

The hydraulic barrier that is supposed to stop sea water from seeping into the aquifer beneath the Model Lands basin is crumbling. Over the past 10 years, water managers have not increased water levels in L-31E canal to keep pace with rising sea level. In fact, water levels in the canal at the S20 structure have been gradually decreasing.

This spring, for example, on 6 April 2020 extreme high tides in Biscayne Bay raised water levels outside the levee about 6 inches above the water in the canal. The preceding months had been exceptionally dry, and at the end of March 2020 water levels in the L-31E canal were barely above water levels outside the levee.

Higher water levels outside the levee means that direction of seepage is in toward the canal, carrying sea water into the aquifer under the Model Lands basin. This condition persisted for 5 days until rainfall returned water levels in the canal above the level of tides.

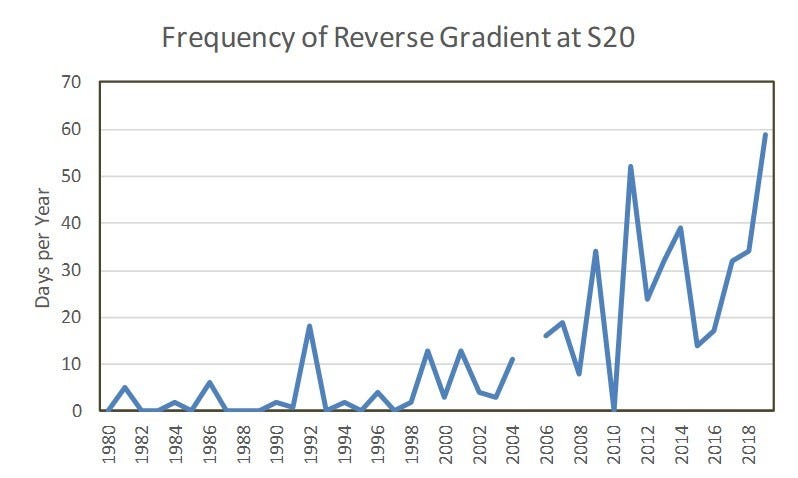

In 2019, there were 60 days on which average water levels outside the levee were higher than in the L-31E canal. Most of these occurred at the end of the dry season, in the spring, when water levels in the Model Lands basin and the L-31E canal are generally low, and during the period of king tides in the fall, when water levels in Biscayne Bay are at their highest for the year.

Periods with a reverse gradient, i.e. water levels outside the levee higher than in the L-31E canal, have been occurring with increasing frequency since about 2000. Two factors contribute to this. First, mean sea level in Biscayne Bay is rising — currently at the rate of 0.33 inches per year. Second, water levels in the L-31E canal at the S20 structure have been dropping at a rate of 0.17 inches per year, measured over the past 10 years.

Over the same time period, salt water has been appearing in the L-31E canal with increasing frequency and intensity. Florida Power and Light measures salinity in the L-31E canal as part of a comprehensive program of environmental monitoring around the Turkey Point power plant. These data show that salinity in the canal has been increasing due to the effect of rising sea level and the occurrence of extreme high tides in Biscayne Bay. Each time water levels outside the levee are higher than in the canal sea water can seep under the levee and into the canal.

What will happen in the future?

If current trends in water levels continue, then by the middle of 2023 there will be no difference between average water levels in the L-31E canal and water levels outside the levee. Beyond 2023, water levels in Biscayne Bay will be higher, on average, and water from Biscayne Bay will seepage under the L-31E into the Model Lands basin most of the time.

Predicting what happens next is complicated by the fact that salt water is already present in the Biscayne aquifer under the Model Lands basin. Because salt water is more dense than fresh water, salt water is found along the bottom of the aquifer at the furthest extent of intrusion into the basin. This is shown as the position of the saltwater interface in the figure below. Fresh water overlies salt water forming a layer at the top of the aquifer, near the ground surface. The thickness of the freshwater layer decreases and the thickness of the layer of salt water increases as one moves toward the coast.

The seepage of sea water under the L-31E levee increases the amount of salt water in the aquifer. This contributes to pushing the saltwater interface farther west under the Model Lands basin. At risk are the municipal well fields that supply fresh water to Florida City, Homestead and the Florida Keys, which are in the path of the advancing saltwater interface.

Because of this threat, the US Geological Survey has been monitoring the position of the saltwater interface all along the shore of Biscayne Bay. Generally, the saltwater interface has been stable, but with the notable exception of the Model Lands basin. Monitoring shows that here the saltwater interface is moving west toward Florida City at between 100 and 140 metres each year.

The future movement of the saltwater interface is influenced by actions being taken by Florida Power and Light to remediate groundwater pollution at the Turkey Point power plant. A number of factors can influence the movement of the saltwater interface. But, hydrogeologists working for the power company have identified that hypersalinity in the power plant’s cooling canals is the factor that has most influences the position of the saltwater interface in the Model Lands basin.

The remediation program uses an array of recovery wells to capture and remove a plume of hypersaline water that escaped into the aquifer from the cooling canals and expanded westward. The recovery wells began operation only recently, in May 2018. It is not known what impact the withdrawal of groundwater by the recovery wells might have on water levels in the L-31E canal and the protection it provides against sea water moving into the aquifer.

Contamination of municipal water supplies may appear to be a distant threat. If the saltwater interface continues to move at the rate that it has been moving, it will reach the Newton well field, a relatively small well field, by around 2026. But, it will be several decades before the interface reaches the larger wells farther west in Homestead and Florida City and the well field that supplies the Florida Keys.

However, water managers must be careful about dismissing the threat of salt water to these well fields in view of the following facts: 1) the saltwater interface is moving in the Model Lands basin and nowhere else; 2) movement of the interface coincides with changes in the hydrology of the basin, by the injection of a plume of hypersaline water into the aquifer, by pumping to remove this plume, and by drier climatic conditions in recent years; and 3) the protection that has been provided by the L-31E canal against sea water flooding the aquifer is crumbling.

What can be done?

In the short term, water managers should immediately work toward raising water levels in the L-31E canal in the Model Lands basin to keep them above rising levels in Biscayne Bay. Maintaining the L-31E canal as a freshwater canal will retard further intrusion of salt water into the aquifer. The L-31E canal anchors the position of the layer of fresh water at the top of the aquifer along the coast. As long as the canal receives enough fresh water to keep it fresh, this will impede the movement of salt water into the aquifer and prevent salt water from completely filling the aquifer.

Over the longer term, water managers should evaluate the vulnerability and sustainability of the municipal well fields west of the Model Lands basin. As a first step, water managers must understand what factors control the movement of the saltwater interface well enough to be able to anticipate its behavior under a range of projected scenarios for sea level rise and climate change. Operationally, this will entail developing a comprehensive hydrologic model for this region and making it available for use by a number of stakeholders.

The most desirable outcome is that water managers use the information developed in this assessment to protect the essential freshwater resource provided by the Biscayne aquifer from the impacts of rising sea level and a changing climate.

However, it is possible that this assessment will lead water managers to conclude that fresh groundwater in southern Miami-Dade County is unsustainable, and that the current well fields must be abandoned. This will set off a scramble to find alternative sources of fresh water for the 160,000 people who live in Homestead, Florida City and the Florida Keys. It is this possibility that should motivate water managers to act now.

References

Andersen, P. and J. Ross, 2018. Variable Density Ground Water Flow and Salinity Transport Model Analysis Attribution Analysis Results. Tetra Tech, June 19, 2018.

FPL Turkey Point Annual Monitoring Report, August 2019.

FPL Turkey Point Remedial Action Annual Status Report, November 2019.

William Nuttle (PhD, PEng) works with water managers, engineers, scientists and others on projects where progress and environmental change intersect.